Steel is one of the most widely used materials on the planet, forming the backbone of infrastructure, transportation, manufacturing, and countless engineered systems.

At the heart of understanding how to work with steel effectively is knowing its melting behavior, which influences everything from casting and welding to heat treatment and high-temperature performance.

What Is Steel?

Before diving into melting behavior, it’s important to define what steel is. Steel is an alloy, a combination of iron with carbon and frequently other elements like chromium, nickel, manganese, and vanadium, in contrast to pure metals like iron or aluminum. These additional elements are deliberately introduced to tailor mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, hardenability, and high-temperature performance.

At its core:

- Iron provides the base metal structure.

- Carbon significantly alters strength and hardness.

- Alloying elements further refine performance, sometimes raising or lowering thermal thresholds.

Because steel is not a single substance but a family of alloys, its thermal behavior, including melting, is more complex than for pure metals.

What Is a Melting Point and How Does It Apply to Steel?

Melting Point vs. Melting Range

The melting point refers to the precise temperature where a pure substance shifts from solid to liquid. Pure iron, for instance, melts at a precise temperature. On the other hand, steel does not melt in one place. Rather, it displays a melting range, which is the range of temperatures at which solid steel progressively turns into a liquid. Iron’s intricate interactions with carbon and other alloying elements are what cause this behavior.

Iron’s intricate interactions with carbon and other alloying elements are what cause this behavior. These interactions shift the internal structure and change how atomic bonds break down under heat.

- Solidus temperature: the lower bound where melting begins.

- Liquidus temperature: the upper bound where material becomes fully liquid.

For most steels, this range generally falls between approximately 1370°C and 1540°C, but the exact span depends heavily on composition. Understanding this range, rather than a single number, is crucial for accurate temperature control in processes like casting, welding, forging, and heat treatments.

Why the Melting Point of Steel Matters

Whether you are designing an engine block, casting a turbine blade, welding a structural beam, or selecting materials for a heat exchanger, the melting behavior of steel influences performance and process decisions. Here are key reasons why melting point matters:

Manufacturing and Fabrication Control

Processes such as casting, welding, and forging rely on predictable melting behavior. Overheating can lead to defects like burn-through, grain coarsening, or unexpected reactions, while insufficient heat may cause incomplete fusion or weak joints.

Structural Integrity in Service

In high-temperature applications such as power plants, engines, and furnaces, structural components may approach temperatures where microstructural changes begin to occur. Engineers must understand these boundaries to prevent softening, creep, and failure.

Energy and Production Efficiency

Steelmaking and recycling involve melting large quantities of metal. Accurately targeting the minimal required temperature range reduces energy consumption, shortens cycle times, and improves furnace life.

Material Selection and Design

Different steel grades exhibit different melting behavior. Selecting the right grade for a thermal environment ensures longevity and performance without over-designing and incurring unnecessary costs.

What Determines Steel’s Melting Behavior?

While general ranges are useful, the precise melting behavior of any given steel grade is influenced by several key factors:

Carbon Content

Carbon is a dominant factor in steel. All steels contain carbon in varying amounts, typically from 0.02% up to 2.1% by weight. The presence of carbon alters the crystalline structure of iron and affects the melting range:

- Low-carbon steels (mild steels) generally melt at temperatures slightly higher within the typical range.

- Higher carbon steels tend to have slightly wider and lower melting ranges because carbon atoms disrupt the iron lattice, lowering the energy required to break bonds.

Alloying Elements

Elements such as chromium, nickel, manganese, molybdenum, silicon, and vanadium are often added to improve strength, corrosion resistance, hardenability, and toughness. These elements can influence melting behavior:

- Some elements raise the melting range by stabilizing the solid phase.

- Others broaden the melting range by forming complex compounds with iron and carbon.

Microstructure and Processing History

Heat treatments, rolling, forging, and cooling rates also play a role. Steel that has been quenched and tempered, normalized, or hot-rolled may exhibit different internal structures that influence how and when phases begin to melt.

Impurities

Residual elements and inclusions from production, such as sulfur or phosphorus, can alter local melting behavior and influence how steel responds to heat overall.

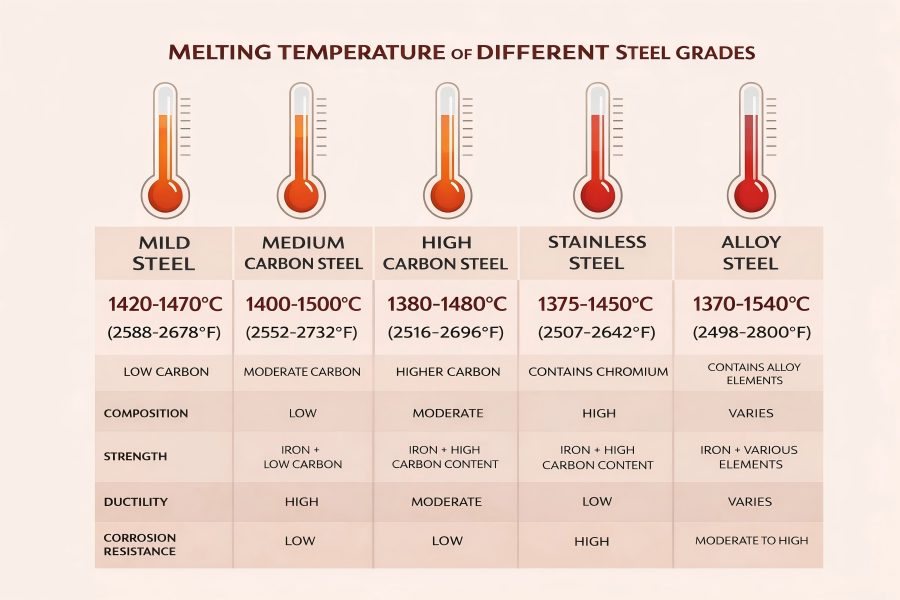

Melting Ranges of Common Steel Types

Below is an overview of typical melting ranges for broad categories of steel. These ranges reflect the cumulative effects of carbon content and alloying additions.

Low Carbon (Mild) Steels

Low-carbon steels are extensively utilized in general fabrication, automobile body panels, and construction. Their melting range is relatively narrow due to modest alloying and carbon content.

| Steel Type | Typical Melting Range (°C) | Typical Melting Range (°F) |

| Low-carbon (mild) steel | ~1420 – 1470 | ~2608 – 2678 |

| General carbon steel | ~1400 – 1520 | ~2552 – 2768 |

Medium and High Carbon Steels

With increased carbon, these steels are used in tools, bearings, shafts, and high-strength components. The increased carbon tends to broaden the melting range slightly.

| Steel Type | Melting Range (°C) | Melting Range (°F) |

| Medium carbon steel | ~1400 – 1500 | ~2552 – 2732 |

| High carbon steel | ~1380 – 1480 | ~2520 – 2696 |

Stainless Steels

Stainless steels contain significant chromium and often nickel. These alloying elements influence thermal behavior, adding corrosion resistance at the cost of a slightly broader melting range.

| Stainless Steel Category | Melting Range (°C) | Melting Range (°F) |

| Austenitic stainless | ~1375 – 1450 | ~2507 – 2642 |

| Ferritic stainless | ~1425 – 1510 | ~2597 – 2750 |

Alloy Steels

Alloy steels contain various elements for specialized properties. Their melting ranges can overlap with carbon steels but may shift based on alloying percentages.

| Alloy Steel Category | Melting Range (°C) | Melting Range (°F) |

| General alloy steels | ~1370 – 1540 | ~2498 – 2800 |

| High-strength low-alloy (HSLA) | ~1390 – 1500 | ~2534 – 2732 |

Comparing Steel with Other Metals

Understanding how steel’s melting behavior contrasts with other common structural and engineering metals helps contextualize its use in high-temperature applications:

| Material | Approx. Melting Point (°C) | Approx. Melting Point (°F) |

| Aluminum | ~660 | ~1220 |

| Copper | ~1084 | ~1983 |

| Bronze | ~1027 – 1050 | ~1881 – 1922 |

| Pure iron | ~1538 | ~2800 |

| Typical steel | ~1370 – 1540 | ~2500 – 2800 |

Steel generally melts at much higher temperatures than aluminum, copper, and bronze, which is one reason it is preferred in high-strength structural applications where elevated temperatures may be encountered.

Industrial Contexts: Why Melting Behavior Matters

Welding and Joining Processes

In welding, localized melting is controlled to fuse two steel pieces. Techniques like shielded metal arc welding (SMAW), gas metal arc welding (GMAW), and tungsten inert gas (TIG) welding must apply heat above the solidus but below the liquidus for optimal fusion without excessive melt-through. Understanding the steel grade’s melting range allows welders to adjust amperage, travel speed, and heat input to produce sound welds without defects like cracking or porosity.

Casting and Foundry Work

Steel casting requires full transformation from solid to liquid. Furnaces must heat steel above the liquidus temperature for complete fluidity, then pour into molds before solidification begins. Too low a temperature leads to incomplete mold filling and cold shuts; too high leads to excessive reactions with refractory materials and energy waste.

Forging and Hot Working

Forging heats steel into a formable state below full melting. The goal is to achieve a plasticized solid state where grains can be shaped without liquefying. Controlling temperatures within the appropriate range enhances mechanical properties by refining grain structure and avoiding overheating or burns.

Heat Treatment and Thermal Processing

Annealing, normalizing, quenching, and tempering are examples of heat treatments that call for exact temperature control in relation to crucial phase transformation sites. Knowing how close these processes bring steel to its melting range helps ensure desired hardness and toughness without unwanted melting or grain growth.

Design Implications for High-Temperature Applications

When engineers design components for environments like turbines, engines, boilers, or furnaces, they must consider not just whether the material will melt but how it behaves near elevated temperatures:

- Creep resistance: prolonged exposure to high temperature can allow materials to deform even below melting.

- Phase changes: certain microstructural transformations occur before melting, altering strength and ductility.

- Oxidation and scaling: high temperatures accelerate surface reactions that can weaken components.

- Thermal expansion: higher temperatures cause dimensional changes that must be accommodated in design.

Selecting a steel grade with appropriate thermal thresholds ensures that components withstand service conditions without unexpected failure.

Measuring and Predicting Melting Behavior

Modern material science uses a combination of thermodynamic models and experimental techniques to assess melting behavior and phase changes. Differential thermal analysis, thermogravimetric methods, and metallographic examination help define solidus and liquidus boundaries for specific alloys.

For practical industry use, databases and standards provide engineers with melting ranges for common grades. Designers can use these values to simulate thermal loads and predict component life under specific temperature profiles.

Troubleshooting Thermal Failures in Steel Components

Thermal failures in steel structures or components often stem from exceeding safe temperature thresholds or improper processing:

Signs of Thermal Overload

Distortion or warp in welded structures

- Grain coarsening and loss of strength

- Surface scaling and oxidation

- Creep deformation over time

- Brittle fracture after repeated thermal cycling

Proper analysis of operating temperatures against melting and transformation ranges often reveals whether a failure was due to exceeding material limits or due to other mechanical or environmental factors.

Selecting the Right Steel for Thermal Performance

Engineers choose steel grades based on a balance of mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, cost, and thermal behavior:

- For high heat exposure, stainless steels and specialized alloys offer resilience.

- For general structural use, mild or carbon steels provide predictable performance at common service temperatures.

- For tool and die applications, high-carbon and alloy steels resist softening and maintain hardness under heat.

Understanding how each steel category approaches its melting range guides material selection and processing parameters.